The African American presence at 1855-1965

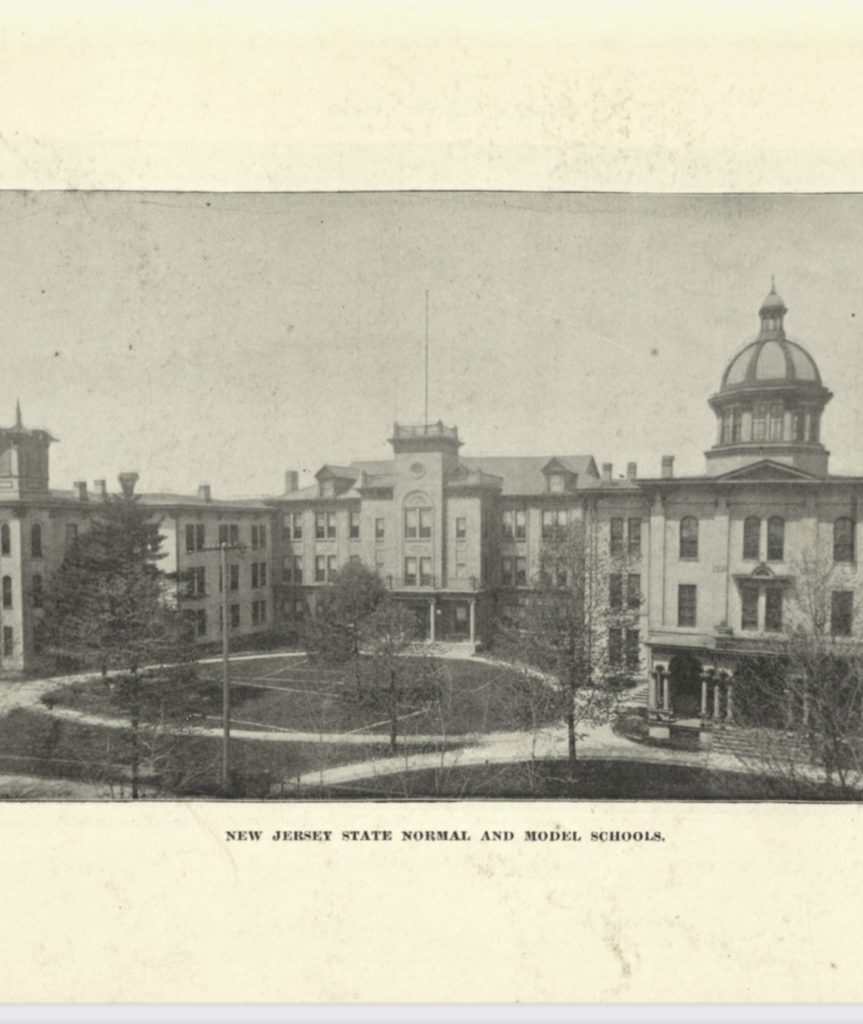

In the course of our archival research on the founding of the Department of African American Studies, we learned some intriguing facts about the African American presence at The College from the days of its founding as the New Jersey State Normal and Model Schools (a Normal school is training school for teachers. The model school was a K-12 school where aspiring teachers could be guided in the application of their classroom learning.) up to the years before Black and Latino students began arriving on campus in significant numbers In the late 1960s. This article is the first in a series about the early African American presence at the College. This was not a comprehensive or scientific content analysis. The series draws materials obtained through keyword searches in both the college’s digital archives and oral history interviews of TCNJ faculty and staff that were conducted in between the 1980 and the early 1990s.

Part 1: 1855-1910

When the New Jersey State Normal School opened its doors in 1855, New Jersey was still a slave state with a reputation for hostility toward African Americans. In his canonical “Short History of Afro-Americans in New Jersey,” historian Giles Wright notes:

Examples of antipathy in New Jersey toward the darker race in New Jersey are easy to find. With the possible exception of New York, New Jersey had the most severe slave code of the Northern colonies. In 1704, for example, a New Jersey law prescribed forty lashes and the branding of a T on the left cheek of any slave convicted of the theft of five to forty shillings. It dictated castration for anyone who attempted or had sexual relations with a white woman. A century later, New Jersey was the last Northern state to enact legislation abolishing slavery; a law passed in 1804 established a system of gradual emancipation. This system allowed slavery to continue down to the 1860s, later than any other northern state. New Jersey slaves were affected by the domestic slave trade that relocated bondsmen down in southern lands opened for cotton cultivation beginning in the early 1800s. Some were even delivered to southern markets, especially New Orleans, as late as the 1820s. From 1852 to 1859, the legislature appropriated $1,000 annually to transport free black New Jerseyans to Africa.

During the Civil War, the legislature passed the so-called “Peace Resolutions,” which disputed President Lincoln’s power to free the slaves of the Confederacy. New Jersey was the only northern state that failed to ratify the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Its most prestigious educational institution, Princeton University… openly discriminated against Afro-Americans in its admissions practices, and between 1848 and 1945 it had no black graduates. The state had separate black public schools, especially in South Jersey, down to the 1950s. And well into the 1960s, Jim Crow education practices governed the access of New Jersey blacks to many movie theaters, restaurants, swimming pools and other public accommodations.

Giles Wright, A Short History of Afro-Americans in New Jersey, (pdf) 1988, p.11

So perhaps it’s not surprising that was not until 1879 that it had its first Black graduate, Priscilla Herbert, daughter of a well-regarded Trenton family and sister of Henri Herbert, publisher of the city’s first Black-owned newspaper, The Sentinel. Detailed information about Herbert has been difficult for historians to trace beyond the scholarly paper linked to her name, above. John Ball, the author of that paper for the TCNJ Journal of Student Scholarship, observes:

In fact, much of Trenton’s history and its cultural legacies are entwined with that of the African American community which grew in a mutually beneficial relationship with the city’s Caucasian social elites since pre-independence. Events such as the duty-free importation of African slaves encouraged by the English crown in the 18th century, the escapes of slaves in the antebellum period, and the flight of blacks from the American South’s Jim Crow racial policies are today used as historical evidence to account for the degrees of diversity observed in New Jersey’s cities.However, the story of how these citizens developed and flourished in a nation often geared towards their collective stagnation have been either disregarded or forgotten in northern cities dominated by ethnocentric racial views until recent decades. The narrative of African American history in Trenton and at The College of New Jersey is an example of how black citizens made invaluable contributions to the region’s complex cultural history and yet were nearly forgotten about.

John Ball, Priscilla Herbert: The College of New Jersey’s first African American graduate

Still, the archival investigations that have been done so far have not produced direct evidence of how the founders of the Normal School thought about Black people, or race more broadly, either as students or as a subject of study. We can infer from commencement photographs that there were no faculty of color. It is not clear who the people were who carried out the tasks of daily maintenance, or whether, in the first decade of the school, they were enslaved or free. Unlike Princeton University, (known as The College of New Jersey until 1890), researchers have not found a documentary record of the school’s leaders debating the capacities of Black people and their suitability for college study. Instead, the Signal and the early college reports talk a great deal about the need for expanded educational opportunities and how that propels the mission and growth of the school.

One thing that clear from the archives is that the educators and students at the College saw themselves as heirs and stewards of a noble legacy of progress in the state beginning with European colonization. This is particularly apparent in the narrative put forward about the history of relations between European settlers and the indigenous communities that inhabited New Jersey. In 1910, the school acquired a mural, The Peace Council of New Jersey and the Indians, 1758 by local artist Richard Blossom Farley, according to research conducted by TCNJ alumna Megan Scarborough for her binge-worthy podcast about the mural, Not a Foot of Land. As quoted by Scarborough, Farley said the painting, “deals with a little known subject that Jerseymen may well be proud of, for it is said that there is not a foot of land in New Jersey that has not been fairly granted to us by the Indian.” That view was echoed in an October, 1910 essay for The Signal outlining the centuries-long history of treaties and purchase agreements that supported the writer’s conclusion that “Every native of New Jersey may take a just pride in the honorable record of his state in relation to the Indian. And the Indians deserve a place in Jersey’s history.” (p.2)

However, Lenni Lenape historian Rev. Dr. John Norwood has explained that while relations between the indigenous people and European settlers (the Quakers, especially) were less violent than in other parts of the country, the Indians who were party to those agreements did not understand themselves to be ceding their rights to their lands. Their understanding was that they had agreed to share the land. They did not have a concept of private property, nor did they recognize European imperial property claims. (Note: the interview linked in the previous sentence refers to lawsuits by the Nanticoke Lenape against the State of New Jersey to restore state recognition. The lawsuits were settled in 2018 and the state recognition was restored.)

Although we did not find the same kind of explicit declaration about about Black peoples and their cultures,hints about the normative view of African Americans show up in the school archives almost from the beginning. The school’s 1857-58 Third Annual Report to the Board of Trustees includes a list of proposed questions for the final examination of the first graduating class. For example, this list of questions for the vocal music section includes the following:

By the 1890s, Normal School students would have had an opportunity to hear “Negro Melodies” sung in classical style when the famed Fisk Jubilee singers performed at the Masonic Hall. In the second part of his documentary history of Trenton, Jack Washington notes that the performance drew a large interracial audience, although Black patrons were required to sit in a segregated section. This 1909 recording gives an indication of what patrons might have heard during that performance:

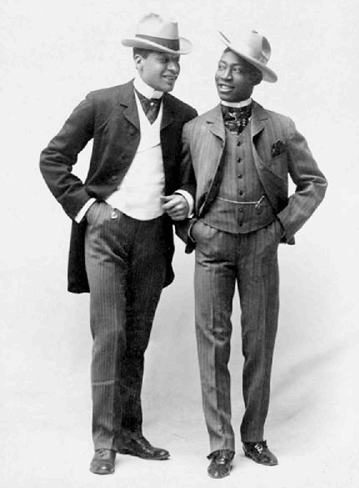

Turn of the century students would also have had an opportunity to see the famed Black minstrel act, Williams and Walker, In 1902, they brought their musical, In Dahomey, to the city’s most storied venue, the Taylor’s Opera House. Although Caribbean-born Bert Williams and George Walker were refined and educated men in real life, the demands of the entertainment industry of their day required that they put on burnt cork and pander to white supremacist stereotypes of Black Americans. Historians say that blackface minstrelsy was invented in the 1830s by working class White entertainers who found wealth and fame doing crude impersonations of Black people. By the time Williams and Walker came along, audience and venue-owners’ expectations were very clear. Despite the indignity of the roles they were forced to play, Williams and Walker’s theatrical partnership is credited with helping to invent American musical theater. Walker himself said:

How to get before the public and prove that ability we might possess was a hard problem for us to solve. We thought that as there seemed to be a great demand for blackfaces on the stage, we would do all we could to get what we felt belonged to us by the laws of nature. We finally decided that as white men with black faces were billing themselves ‘coons,’ Williams and Walker would do well to bill themselves as ‘The Two Real Coons’ and so we did. Our bills attracted the attention of managers, and gradually we made our way in.

George Walker, 1873-1911

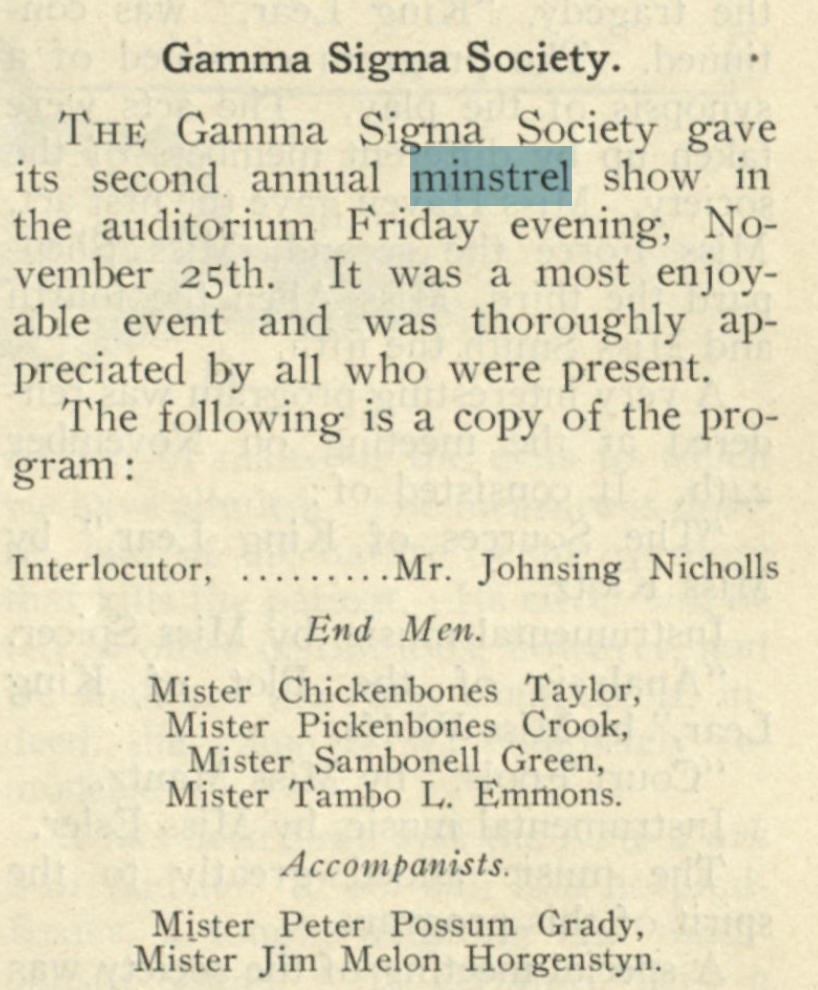

As early as 1904, the Gamma Gamma Sigma sorority’s minstrel shows became a highlight of campus life. This report from the December, 1905 Signal is illustrative. There are similar reports of the sorority’s annual minstrel shows for the next few decades.

The program includes the song “Nobody,” a 1905 hit tune performed by Bert Williams in Abyssinia, one of his productions with Bert Walker. It remains his most popular recording. You can listen to a 1913 recording of Williams singing the song below.

An essay on lynching and sentimental journeys

In the 19th and early 20th century, Signal writers did take on some serious issues with regard to race. One example is a July, 1894 essay, “Lynch Law,” by a Model School graduate identified as Nemo ’91. The author’s fundamental argument is that it undermines the rule of law. The underlying motive for lynching is vengeance, the author says, and that only incites further violence. Taking a paternalistic tone, the author argues that “we need law equally enforced against lynchers and all of the criminals as well. It is also necessary that some elevating influence be brought to bear alike on the white and the negro (sic) populations of the south; upon the former that they set a better example for the latter, and upon the latter that they cease their outrageous treatment of the former.” (p. 107) The author does not seem to be aware that by 1894, journalist Ida B. Wells had documented many instances in which the alleged “outrageous treatment” was a fiction contrived to justify murders that were often acts designed to terrorize Black communities into complying with Jim Crow laws and restrictions.

Paternalism is also evident in the late 19th and early 20th travelogues and short stories, mixed with a bit of “Lost Cause” nostalgia. An 1892 travelogue takes us to the home of “one of Georgia’s greatest statesmen – if not the greatest.” Incredulously, this great man has no monument., but the author assures us that will soon be made right. Who is this great man? A “negress” (sic) informs us, “Mars Alex,” aka Alexander H. Stephens. The writer feels no need to inform the reader that this is the late Vice President of the Confederacy. Also, the writer and editors are either unaware or unconcerned that the term used to describe the Black woman in the story was considered pejorative. A 1904 short story, Uncle Joe and the Railroad, presents a dialect-speaking elderly Black man who is convince that the new mode of transportation will lead to ruin. Examples abound, and what seems common to them is that there is a great deal of discussion about Black people (and about indigenous people, Jewish people, and other minoritized groups, for that matter), but no clear examples o members of those groups speaking for themselves.

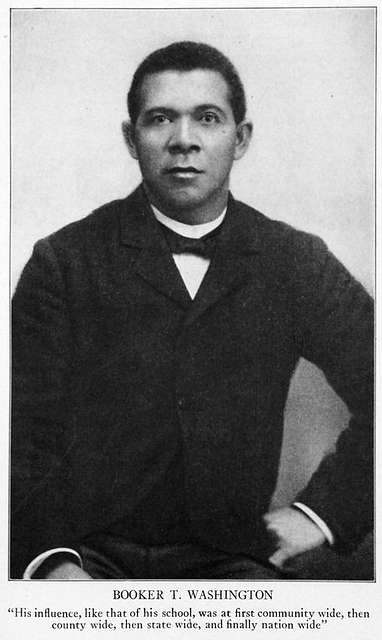

The Signal and the annual report do document one occasion of a prominent Black speaker – a 1903 lecture by Booker T. Washington, the principal of Tuskegee Institute, on the “Negro Problem.” That report is at the top of this post. Local history buffs also say that the prodigious scholar-activist W.E.B. DuBois also spoke on campus, but evidence of that hasn’t been found. Coincidentally, W.E.B. DuBois published his magnum opus, The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, making the case against Washington’s strategy of accommodation was counterproductive and doomed to failure. DuBois would go on to co-found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 and the Trenton branch would become responsible for some of its pivotal cases in effort to dismantle legal segregation, particularly in education.

Nonetheless, here is what the annual report and the May, 1903 Signal had to say about Washington’s appearance. While the annual report cited Washington’s visit as one of “a number of interesting lectures,” the unsigned Signal writer said the “school was greatly entertained.” The writer went on to add, “We were amused at his disapprobation of a negro (sic) being employed to ‘clean out’ a ‘chicken house’ in the daylight – trouble ahead.” On a less jocular note, the writer added that Washington’s argument that Black people needed to elevate themselves through hard work and industrial education “seems such a just one that it would be impossible to be refuted.” What the Signal writer couldn’t have known at the time was that Washington was secretly funding lawsuits against segregation and voter suppression while feigning acquiescence to segregation.

In the next decade, the African American presence would finally speak in the voice of a Black student – Dorothy Frisbey, class of 1917. The next post is about her life.