Searching for Dorothy Frisbey ’17, the first Black Writer for the Signal

Our last post on our investigation of the early history of the African American presence at the The College of New Jersey disclosed that while the curriculum and popular entertainment on campus reflected ideas about African American people and culture, the only extant evidence of serious consideration of African American thought was a May, 1903 report on a lecture by Booker T. Washington that endorsed his policy of accommodating racial segregation in the hope that Black Americans would be allowed to gain a financial foothold in the American economy. Not until 1917 do we find the thoughts of a Black person recorded in a campus publication. Dorothy A. Frisbey penned the lead essay in the January issue, “The Chances of the Negro After the European War.” A close reading of this text through the lens of both journalism history and African-American history offers interesting clues to her thoughts about race, and perhaps the thoughts of some of her classmates as well. This essay explores both the contents of the essay and how it might have been informed by the circumstances of Black people’s lives in New Jersey at that time.

The essay

“Sixteen-Nineteen,” Frisbey begins, “a memorable year indeed!” She goes on to say,

Nearly three hundred years ago he left his jungle home, willingly or unwillingly, as the case may have been, to the land of opportunity. Opportunity for whom? For the Negro? Scarcely could it be called opportunity for him at that time, for he came not for his own prosperity, but for the prosperity of others. Toiling hour after hour, day after day, year after year, under the hot sun, and in many cases under the lash of a cruel master. he and his posterity grew..

Dorothy Frisbey

Frisbey describes how enslaved people had to engage in subterfuge to become educated, because the slavemaster knew “that an educated mind would not long suffer the body to be oppressed.” Surveying the state of the race 52 years after emancipation, Frisbey observed, “Today, the Negro has his colleges, his large churches, his stores and his country seats; but one thing is sadly lacking – he has not got justice in the industrial world.” And why not? “Foreigners have so flooded the country with their cheaper labor that the Negro has been forced to stand in the background…”

In her conclusion, Frisbey bemoans World War I but suggests that it might yield an unexpected benefit for her race. While this may seem cavalier, it’s worth remembering that at the time her essay was published in January, 1917, the United States had not entered the war. President Woodrow Wilson had won re-election in 1916 with the slogan, “he kept us out of war.” Frisbey might have been thinking that the war would remain a European conflict when she argued that because so many Europeans were being drawn into battle, and because they will need to rebuild their own war-torn countries at wars’ end, US employers will need to turn to Black labor. It is then, she asserts, that Black people’s diligence in acquiring education and skills will be rewarded, the race will rise, and the nation will benefit. On April 2, 1917, Pres. Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war and entered the fray.

Dorothy Frisbey’s life and times

Frisbey’s earnest effort reflects ideological currents of the times, both in its ideas about racial uplift and its antagonisms toward immigrants. A historian might also note that Frisbey’s reference to Africa as a “jungle home” reflects the common ignorance about the continent’s geography. She also repeats the common stereotype that Black people are naturally religious. It was this kind of pervasive ignorance, perpetuated by the leading White historians and learned societies of the day, that led Carter G. Woodson to establish the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915.

Certainly, Frisbey’s argument that immigrant workers were taking jobs that might have gone to Black workers would have been familiar to readers of that time. In his famous 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech, Booker T. Washington begged White Southern employers, “Cast down your buckets where you are” by hiring their formerly enslaved people rather than immigrants. By 1913, Washington was trying to convince leaders of the burgeoning union movement that dropping its discriminatory treatment of Black workers would be to their advantage. Frisbey quotes Washington’s admonitions about the value of hard work and moral rectitude approvingly.

The 1915 New Jersey Census lists Dorothy Frisbey as residing at 27 Passaic Street in Trenton, not far from where the Old Barracks Museum stands today. It’s very likely that Frisbey observed these class, race and ethnic antagonisms during her time at the Trenton Normal School. Normal School students were not cloistered from the community. People were streaming into the city from other regions and other countries, hoping to get jobs in the local factories, foundries, and entertainment emporiums. But segregation and the common dangers of city life also loomed.

Life in the bustling industrial city of Trenton probably contrasted sharply with the life she knew in her hometown of Woodbury, New Jersey, which would have been more rural. Census records indicate that the Frisbey family was working-class and aspirational. In the 1905 New Jersey Census, her father, Robert, is listed as a gardener. Born in New Jersey in April, 1855, it’s possible Robert had been enslaved as a child. Her mother, Dorothy, kept house. Her sister, Laura, was a domestic. Older brother Augustus was a contractor. Her brother Haward was a laborer and she and brother James were still in school. All of the Frisbeys could read and write, so being able to send Dorothy to school to become a teacher was likely a source of great pride. But when she argues in her essay that many White employers would rather hire unlettered immigrants rather than educated Negroes, it’s possible that she’s not just echoing Booker T. Washington. It’s likely that she’s speaking from personal observation and experience.

In the streets and especially, the churches, Frisbey might also have learned of the inaugural meeting of the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs which took place in Trenton in 1915. It’s very likely she would have embraced the organization’s ideas about the duty of Black women to racial uplift. In 1918, founding president Florence Spearling Randolph would write to her members:

The close of this dreadful war will usher in a new era for the Negro people of this country. Are we preparing ourselves? Much of the responsibility of preparedness rests with the womanhood of the race. There are enough of us, we have ability, intelligence, loyalty and love; but we are still too divided. The only way we can ever hope to succeed is by banding ourselves together as a unit. Every State in the Union ought to be organized and become a part of the national body. The educated, trained Negro woman, whether trained in the school house or by personal effort, owes it to her less fortunate sister to join hands with her in the struggle for a better womanhood, better homes, a better community life, — a united struggle for equality before the law, to down race discrimination, segregation, jimcrowism, mob violence, and lynch law. But it must be pull one, pull all, pull long and all together and it is certainly worth the struggle.

Florence Spearling Randolph, report to the Third Annual Convention of the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs

Among the Trentonians Dorothy Frisbey might have encountered during her time in Trenton was a boy named Needham Roberts, son of Reverend Norman Roberts. Born in 1901, Needham had worked as a bellhop and soda jerk. In 1916, enlisted in the all-Black Black Rattlers unit of the 15th New York National Guard: they eventually became part of the famed 369th Infantry regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters. During World War 1, Hellfighters were known for both their military valor and their band, led by James Reese Europe. Roberts and another Black soldier, Henry Johnson, would earn the French Croix de Guerre for their performance in a particularly pitched battle against German soldiers in the Argonne forest, near an area known as “no man’s land.”

Anti-Black racism and anti-immigrant prejudice

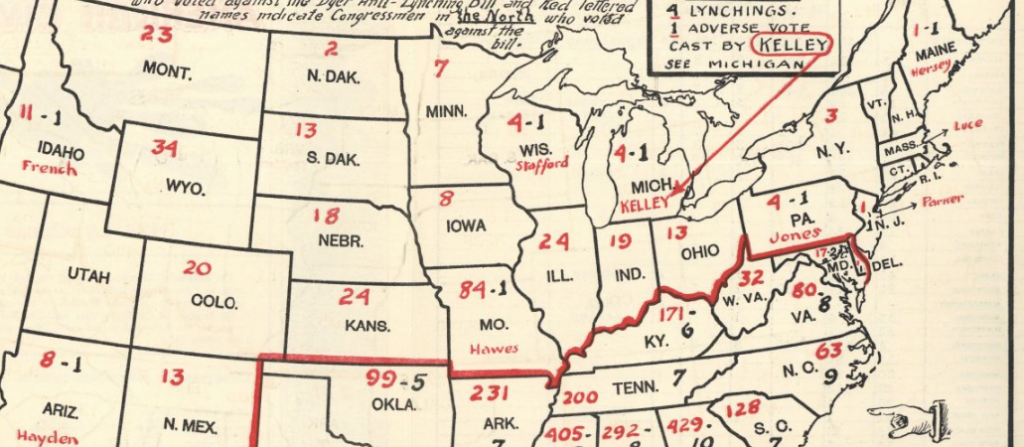

Frisbey was writing at time of anti-Black racism that had all but eviscerated the hope of the Reconstruction era – a period that historian Rayford Logan called the Nadir in his book, The Betrayal of the Negro – from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson. As historian Giles Wright has documented, New Jersey was a site of longstanding proslavery and pro-segregationist policies. Pres. Wilson had courted Black votes in the 1912 and 1916 presidential election, only to anger and bewilder Black supporters by imposing segregation in federal offices. Before ascending to the White House, Wilson had served as Governor of New Jersey where he built a reputation as a progressive politician. Before that he had been president of Princeton University, where he denied admission to William Robeson, Jr., son of the Black pastor of Witherspoon Presbyterian Church, because of his race. Robeson was the older brother of Paul Robeson, the illustrious entertainer, athlete and human rights activist. In 1902, he published a five-volume History of the American People. Its Neo-Confederate version of the Civil War and Reconstruction was liberally quoted in D.W. Griffith’s wildly popular and widely protested 1915 film, Birth of a Nation. Wilson showed the film in the White House, reportedly calling it “history written in lightning,” and helped to fuel a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. Antiblack violence was pervasive, and efforts to get Congress to pass an anti-lynching law were meeting stiff opposition. This 1922 map provided to the Dyer Antilynching Committee by the Michigan Association of Colored Women’s clubs is illustrative:

European immigrant workers did not have an easy time in Trenton or anywhere else in the United States. In his widely-acclaimed 1908 book, Along the Color Line, muckraking journalist Ray Stannard Baker argued,”[T]he vast majority of Negroes (and many foreigners and whites) … have little or no appreciation of the duties of citizenship. [T]hey should be required to wait before being allowed to vote until they are prepared.”(p.303) In 1916, Frank Julian Warne bemoaned the influx of Italian immigrants into the Chambersburg neighborhood in Trenton. Thousands of “native-born” White New Jerseyans joined the Ku Klux Klan, drawn by their anti-Black, anti-Jewish, anti- Catholic and anti-immigrant views. In 1924, 10,000 Klan members would march in Hamilton, New Jersey. This was the same year that Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act cosponsored by Princeton University graduate and Pennsylvania Senator David Reed — a law designed to restrict immigration from Southern Europe and Asia. Eventually, historian Rayford Logan notes, white ethnic groups could be assimilated, but Black people remained outside, and unassimilable.

In his 2010 book, The Condemnation of Blackness, historian Kahlil Muhammad argued that this idea that Black people are incapable of being fully human and American gained the imprimatur of science in the early 20th century, through the invention of the science of statistics. The book focuses particularly on the ways in which racial logics were woven into seemingly neutral public policy tools, such as the Uniform Crime Report.

The capitalization clue

There’s another thing about the Signal article – something that might seem trivial now, but would have been quite significant at the time: the capitalization of the word “Negro” . First, the previously-cited 1903 Signal article on Booker T. Washington’s lecture used “negro” with a lower-case “N.” Other early issues of the Signal referred to Black people by other pejorative terms – n*****, darky, Sambo, etc.

It’s very likely that Dorothy Frisbey used the upper-case N deliberately. As historians Bettye Collier-Thomas and James Turner note, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a fierce debate among Black leaders about racial designation. With the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitition, Black people became legal citizens of the United States for the first time. Some leaders, such as T. Thomas Fortune, argued for Afro-American as an identity, while others were afraid that adopting “Afro” would legitimize those who argued that Black people could not be be fully assimilated into the body politic. The widely-read journalist John Edward Bruce – also known as “Bruce Grit,” (1856-1924) had been a leading advocate of the term Negro since the 1890s, stressing the importance of the capital N. Bruce argued that “Afro-American” was a term adopted mostly by mixed-race people and Negro was more inclusive. Bruce became an editor and columnist for the Negro World, the official organ of Marcus Garvey’s Back-to-Africa movement. Garvey, too, would champion the use of Negro, and by 1915, the term had become widely accepted among Black people.

The Souls of Black Folk, also published in 1903, uses a capital “N” as in “After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world…” It is hard to overstate the importance of the Souls of Black Folk at the time of its publication and since. It’s very likely that Frisbey read it. The capital N, as DuBois deploys it in this text, is intended to assert that African-descended people in the United States constitute a distinct cultural group that has contributed positively to to the nation, and that can do even more if released from the yoke of oppression.

In her book, Within the Veil: Black Journalists, White Media (NYU Press, 2000) journalism historian Pamela Newark relates the efforts of Lester Aglar Walton (1882-1965) to get White newspapers to capitalize Negro, beginning in 1913 (p. 48). Walton was one of the first and few Black journalists to work for White newspapers, starting with the St. Louis Star in 1902. The Associated Press took up the proposal in 1913 and rejected it. Walton kept up a letter-writing campaign for several years. The New York Times began capitalizing Negro in 1930.

We can’t know whether the Signal editors chose to allow the capitalized “Negro” out of solidarity or for some other reason. The fact that hers was the lead essay suggests that she was held in some esteem. In another part of the issue, on a page devoted to describing each of the graduates, Frisbey is described as, “a good student with exceptionally good judgment, but never proud or boastful.” Another story speculating on the future lives of the graduating class predicts that Frisbey, along with the “Misses Generette, E. Gould, and J. Gould,” will be “well known in the South for their excellent work and wonderful training in the Normal School.” This suggests that Frisbey as well as the other women were Black, and that they’d expressed interest in teaching Black students below the Mason-Dixon Line, an aspiration that would not have been uncommon among those African Americans fortunate enough to get an education. Indeed, in the group photo of the graduating class are four women who are phenotypically Black, and two who resemble each other enough to suggest that they are related.

After her graduation from the Normal School, Dorothy Frisbey returned to Woodbury and became a teacher. If she had any aspirations to go South, to exercise the right to vote that women would receive in 1920, or to involve herself in the Black women’s club movement, they would not be realized. According to a record obtained from Ancestry.com, Frisbey died in March, 1920, at the age of 24. Census records from the time of her birth in December, 1895 to the time of her death suggest that her time at the Normal School was the only time that she didn’t live at home.

Dorothy Frisbey’s life was short, but her Signal essay remains a valuable artifact. She appears to have been the Signal’s first identifiably Black writer. She was clearly what would have been called a “race woman” dedicated to racial uplift, and her contribution to the Signal prefigures issues that Black students would raise in the coming decades. It might be illuminating to research the lives of the other three students as well. It’s not until the 1950s that another Black student emerges from the archives to make a significant impact on campus life and beyond, but that’s a story for a different post.