Don Evans: Writing Black Stories that Everyone Could Enjoy

By Matthew Kaufman

“A Modern Playwright in a Classical Vein.” That was the title of a 1980 New York Times article about playwright and TCNJ professor Donald T. Evans. Prof. Evans was a man of many passions and talents, from writing plays and poetry to teaching African American Studies at the College, aka Trenton State. Prof Evans’s work reflects not only his respect for the classics, but also his call to action at a time of great turbulence in American education and society.

A professor of English, theatre, and African American Studies, Prof. Evans had written more than a dozen plays at the time of his death in 2004. As a contributor to the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s, he was passionate about telling Black stories.

Prof. Evans’s son Todd, also involved in theatre, said that one of the reasons his father began writing plays was because of an experience he had teaching Shakespeare.

“He was teaching Shakespeare to a class of Black students who were having trouble getting it,” said Evans. “So, he adapted it and moved it up to the 70s, and he made his own version of Taming of the Shrew. One of the reasons was to familiarize some of the young Black students who could not relate.”

The play, titled “It’s Showdown Time,” takes place in a Black neighborhood in Philadelphia, and it debuted in 1976, becoming one of Prof. Evan’s best-known plays. “Showdown” is the story of a barber who moves to Philadelphia and tries to woo over the “sharpest-tongued” woman in the area, according to the play’s official description.

Evans also said his father began playwriting because of the role that theatre had in protest.

“The other reason why he used plays was because in the 60s in the 70s—not so much nowadays—Black Theatre was another form of protest,” Evans explained. “There were a lot of civil rights plays being written by Alice Childress and ED Bullins.”

Indeed, in the New York Times piece, Prof. Evans goes into detail about the way that theaters treat Black playwrights and performers, noting that theater owners often did not place as much trust in the artists as they did white playwrights.

“When Black plays are produced, theaters assume that we must still be taught basic elements,” Prof. Evans told the Times. “They don’t appreciate the fact that we know what we’re doing, or that Black American playwrights have their historic tradition that precedes even the work of modern artists like Lorraine Hansberry, who, incidentally, is seldom revived.”

Prof. Evans also described this issue in a 1998 article, titled “Been There, Done That,” published in Black Theatre Network News. In this essay, the playwright goes into detail about the issues surrounding Black Theatre at that time and what he believed needed to happen to combat them.

“It is safe to say that the black playwright of this generation works in an industry and art form that has little interest in what he or she has to say,” Prof. Evans wrote. “It is content to continually present a sanitized and, therefore, distorted view of life and art in America.”

The professor also describes in that piece the importance of college and local theaters in advancing Black Theatre, as opposed to big-budget, well-known theaters; however, he told the Times that Black artists still faced many challenges at the college-level.

“I’ve always tried to make college theater something multiracial and multicultural—a living art form,” Prof. Evans said. “But no one pays serious attention to Black college kids who love the theater. They perform in isolated groups. In terms of their craft, their work isn’t seriously appraised.”

What also concerned his father, according to Evans, was the growing popularity of plays that turned the Black experience into a joke, with his father calling it a “minstrel show atmosphere.” Evans noted that his father once declined an offer from a well-known producer who wanted to take one of Prof. Evans’s plays and “dilute it with jokes that weren’t really supposed to be there.”

That kind of treatment, the son said, led Prof. Evans to fear that Black Theatre would “miss the seriousness of the message” that many Black playwrights were trying to portray.

Indeed, Evans said one of the ways he tries to honor his father is by supporting and emphasizing community theatre troupes with amateur actors. He is the founder of the Don Evans Players, a community theatre troupe dedicated to eternalizing Don’s plays.

“He was off Broadway, he did touring plays with professional actors, but when I saw my father the most in his element was when he was directing the students or when he was directing community theatre,” said Evans. “With the Don Evans Players, there are a few professional actors, but most of it is just people who want to try out acting or might have acted as a child and want to act again.”

Evans noted that one of the reasons his father’s plays were so loved was because they appealed to a wide demographic of audiences. Not only did they increase representation by telling Black stories, they also let in a wider audience of people who may not have heard these types of stories before.

“It was a double-edged sword, because it also let some of the white people who weren't familiar with what was going on in the Black neighborhoods or the Black community,” said Todd Evans. “And they can see that in some of my father's plays.”

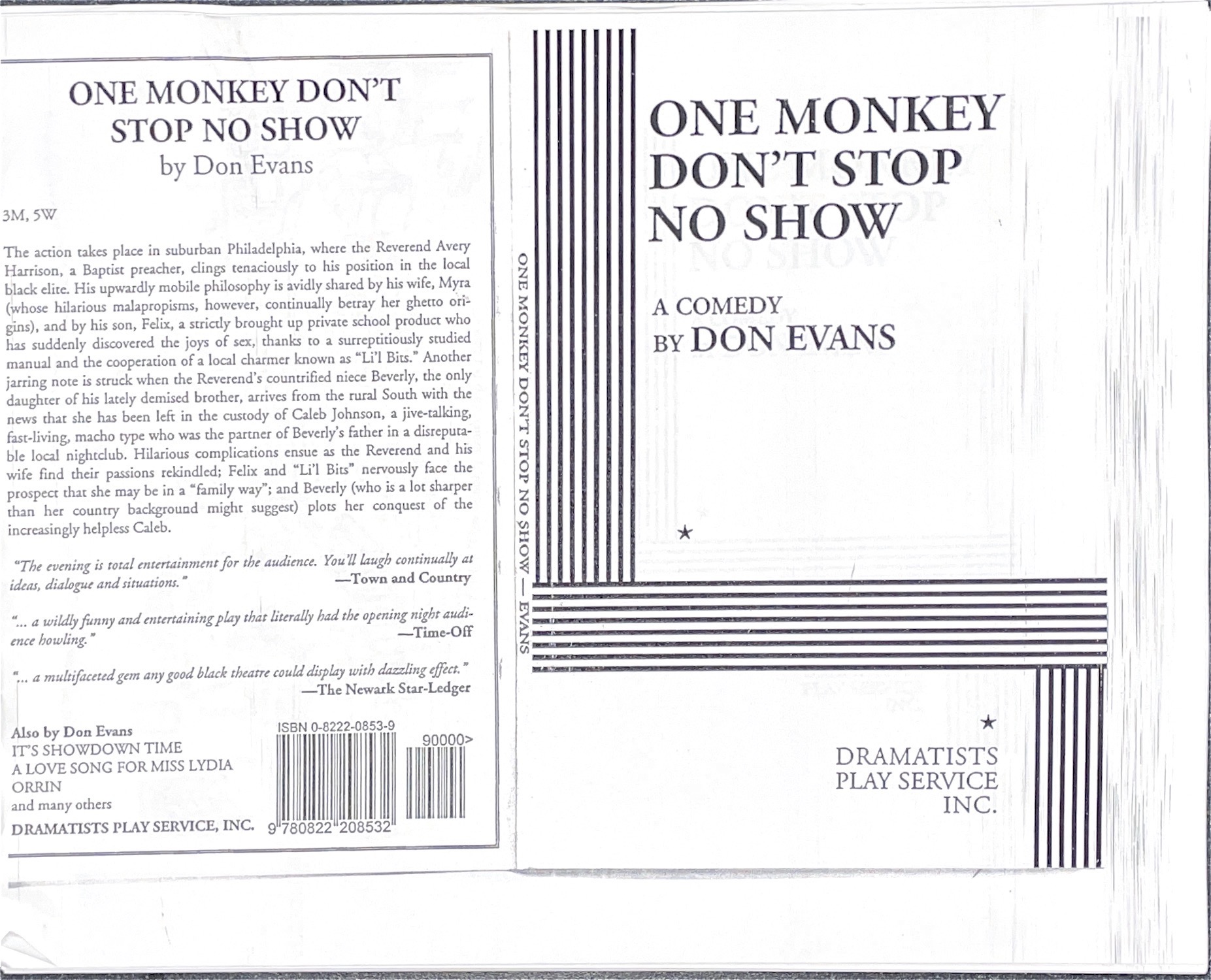

The wide appeal is clear from the plot of many of his father's plays. “A Love Song for Miss Lydia” is about an elderly widow in Philadelphia who takes in a boarder to earn some extra money and have a companion, with critics noting the “humanity and humor” in it, and the Times described “One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show” as “a comedic spoof of a middle-class black family, with a serious undercurrent.”

And it was not just the plays that were popular with a wide demographic. Evans noted that his father was popular with everyone at the College, and this is why he left such an important mark on the school.

“One of the most important things with my dad was that he was a liaison between the students and the faculty and staff, and he was loved by both the white students and the Black students, and he tended to bring them together a lot,” said Evans.

“And that’s what I think his greatest asset was, that he was able to communicate with so many different kinds of people.”